In part one of this two-part post on kitchen knife construction we covered balance, with a focus on the tang, and the two categories of steel that are used in kitchen knife construction. We also detailed a list of some of the more popular steels that are used in good quality kitchen knives with specifications on hardness, easy of sharpening and edge retention.

This is part three in our series on kitchen knives and concludes our two-part post on kitchen knife construction. In this post we will cover the various Cladding types, Grinds and Handles. If you have already read our posts on Kitchen knife basics, and part one of kitchen knife construction you will have a pretty good idea of what you are looking at when you pick up a knife. By the end of this post, you should be able to, at a glance, visually discern how a knife is built, how well balanced a knife is and if that balance and design suites your needs.

Cladded or Core-less?

A couple of other terms that you might hear as you shop for kitchen knives are cladded and core-less or mono-steel. These two terms relate to the way the blade of a knife is forged. A vast majority of knives on the market are produced from a single sheet of flat steel, which has the blades of the knives punched out of it. The blade is then cleaned up on a grinder or sanding belt, heat treated and sharpened. This is a core-less knife and is a technique used by mass production knife makers.

Core-less knives are also made in the premium market. Sometimes this means that the steel has been forged into the shape of the knife via heat, hammer and anvil. Other times this means that the knife has still been cut from a sheet of metal. Either way the knife is formed from a single piece of steel.

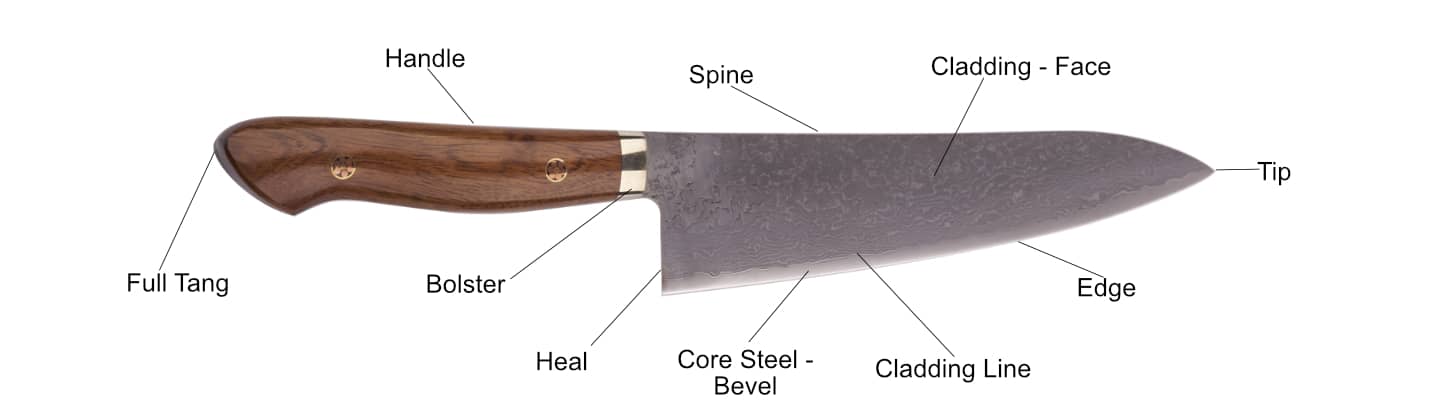

Traditional Damascus knives are core-less knives. Two or more pieces of steel are forge welded together and folded many times to produce the beautiful and strong, multi-layered effect. However, many modern blades, which have a Damascus finish are simply Damascus clad and another more pure and hardy steel is sandwiched into the core of the knife. Often this is visible if you look at the spine of the knife or cladding line.

In Japanese this technique is call San Mai and is a very popular technique for producing beautiful, strong and ultra-sharp blades. San Mai allows the blacksmith to forge the blade from a very hard steel, often a high carbon steel, and then add a protective stainless-steel cladding to the outside of the blade. These knives are often more expensive than straight high carbon steel blades, but they benefit from the advantages of both high carbon steel and stainless-steel.

Blacksmiths use Damascus for the cladding because it is so beautiful, hard and resists rust. However, there are several other steels used and often the blacksmith will finish the blade with decorative hammer work, which is called a Tsuchimi or hammered finish. Like the Damascus, Tsuchimi, looks very nice and actually both finishes also have another practical purpose other than to protect the core of the blade. The uneven texturized outer layer also helps to stop food sticking to the outside of the blade.

Blade Geometry (Grind)

Kitchen knives come in a myriad of blade geometries and, while there is a selection of more traditional or popular designs, knife designers are getting more and more experimental when it comes to blade geometry. Blade geometry will play a significant role in the way that the blade of a knife moves through a given material. Blade geometry can become quite complex, but basically comes down to two main elements. There is the bevel and the edge. The bevel is the angle of the knife and not to be confused with the angle of the edge. An easy way to differentiate between the two is to understand the bevel angle is not active in the cutting process, but more about pushing the already cut material away from the knife. The edge on the other hand is all about actively cutting through the material.

90% of all the mainstream branded knives you will find on the market will have a Double Bevel. However, some knives, especially those produced for the Japanese market come with a Single Bevel. Rarer still is an Asymmetrical or Differential Bevel, but this is becoming more popular in the hand forged and premium knife market. As described above the bevel plays a role in moving the cut material away from the knife.

A Double Bevel will part the material evenly. This is good for general purpose knives like a chef’s knife or Gyuto and isn’t really going to provide any extra advantage to a particular cutting task but works well for the more common kitchen tasks.

A Single Bevel is design to move material to one particular side, either the left or right depending on whether it is a left-handed or right handed blade. Single bevel knives are typically designed for slicing and butchering meats and fish. Yanagiba or Yanagi (Japanese Sashimi knife), Deba (Japanese Fish Filleting Knife) and Nakiri or Nagiri (Japanese Vegetable knife) are common single bevel blades. In all three cases the single bevel is essential in performing the tasks the knives are produced for. As a side note all three of these knives often have a hollow grind (Urasuki) on the back side of the blade, we will discuss this a little more in the next section.

Like the Double Bevel an Asymmetrical or Differential Bevel is not really used on special purpose blades and is mostly found on more general-purpose knives. Often these knives have a larger angle bevel on the front side and a more acute angle on the back side of the blade. This design could be seen as some form of a compromise between the Double and Single bevel designs. Asymmetrical blades are often seen as more premium blades, but really it boils down to personal preference. You could argue that if you do a lot of slicing work in the kitchen then an Asymmetrical blade would benefit your needs, while those who do a lot of chopping would prefer a double bevel knife.

Flat and Convex

Once a blacksmith or knife designer has chosen double, single or asymmetrical grind they may wish to consider whether to simply give the knife a Flat edge or a convex edge. This is a question of sharpness or rather what you consider sharpness and again it is probably also a question of how the knife will be used.

A Flat edge will be as described the surface of the edge is completely flat. This gives the knife a very acute angle but adds surface area to the blade and there for more drag. A convex grind is curved to the edge. This gives a far smaller surface area, but a wider cutting angle.

So, which is sharper? Technically you could argue that the flat grind with its more acute cutting angle is sharper, but because of the added drag that the greater surface area brings you might argue that the convex grind is sharper. So, once again it boils down to usage.

Note: The flat grind is much easier to sharpen.

Handles

Knife handles come in a myriad different shapes and sizes; they are made from almost every material imaginable. Knife handles play an important role in terms of ergonomics and fatigue reduction. Knife handles also help in terms of style and character and they provide a contact point, a tactile surface that allows us to wield and manipulate our kitchen knives.

Shapes

Although there are a lot of variations, kitchen knife handles come in two basic shapes. There is the traditional western style, which offers ergonomic contours designed to support and fit the fingers and palm of the user’s hand. Then there is the Japanese Wa handle, which is often a hexagonal, octagonal or “D” shaped cylindrical handle. The ridges of the Wa handle also serve to fit and support the user’s hand and the cylindrical form makes it easy to manipulate the blade as it can be rolled between the user's fingers.

Materials

Kitchen knife handles come in an almost endless variety of woods, bones, bonded composite, and plastic materials, as well as metals. There are only three main points to consider here.

Firstly, if you are a professional chef there may be some regulations on the types of material you are allowed to work with. Hygiene is of particular concern and should be considered before making your purchase, but don’t be too quick to rule out a wooden handle. Some woods contain natural antibacterial properties and could be better than plastics or composite materials. Additionally, most wooden handles are coated and even impregnated with oils that provide an antibacterial seal.

Secondly, and this is important, is comfort and ergonomics. If you are purchasing a hand-forged blade or you are a professional chef, the last thing you want is a poorly designed handle that lacks the ergonomics needed to keep you comfortable.

Finally, is looks or style. This is not a major point in terms of practicality, but let’s face it, if you are looking to purchase a premium or hand-forged kitchen knife, which you might end up passing on to your kids, style is going to be meaningful.

Bolster/Ferrule

The bolster is mostly found on the western style handles and can be a quite nice feature. The bolster or in some cases bolsters can be found at the front of the handle and sometimes at the end of the handle (bolsters at the end of the handle are sometimes called a pommel). A bolster serves two purposes. Firstly, they help to reinforce the handle and secondly, they can help to balance the knife by increasing weight at the rear to offset the weight at the tip.

However, if a forward bolster extends into a finger guard, while this can be comforting for a hobby cook, as your knife skills improve you may find the finger guard reduces the versatility of the knife. This is particularly true in terms of long slicing cuts, where the finger guard reduces the length of the potential slicing movement.

The ferrule is a feature mostly found on the Japanese Wa handle and is in almost the same position as a forward bolster. A ferrule is simply used to increase the strength of the handle at its most vulnerable point. Often a ferrule is used to give a Wa handle a unique feature and style and is often made from rare woods, bone, and even coral or stone can be found on some artisan handles.

Western or Wa which is best?

Really, this comes down to taste, comfort, and purpose.

Often western style knife handles are harder to make and harder to replace if they become damaged. Often a western handle is fastened with pins and glue and essentially this means that if it becomes damaged you will need to send it back to the manufacturer.

The handle on the Japanese Wa handle slides over the tang and is fastened with epoxy resin or some other bonding agent and so if it becomes damaged can even be replaced at home.

In terms of comfort the Wa handle is also more flexible. Some cooks may find that western style handles are too small or big in terms of the ergonomic ridges and general shape and length. Essentially, they are designed to fit a typical or statistical majority and don’t necessarily fit with every hand shape or size. The Wa handle on the other hand, while less focused on every contour of the hand is often a comfortable one size fits all shape and length.

Conclusion

So, by know if you have been following our series on kitchen knives you should have a fairly good understanding of how they are made and how the various design elements will affect their balance, ergonomics and usage. If you missed any of the previous chapters on the basics or the first half of this two part post on kitchen knife construction feel free to jump back at any time.

Shameless Plug: Looking to buy a kitchen knife?

Sign Up for a free membership and get 5% of your first order.